TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Petition

to Remove the American Peregrine Falcon

Pertinent

information for a Petition to Amend a rule as required California Fish and Game Commission

Nationwide Peregrine Falcon populations began to decline as early as the late 1940s. The magnitude of the decline was not fully realized until the 1960s when European Peregrine Falcon surveys also reported substantial reductions (Newton 1988). The historic Madison Conference in 1965 detailed the decline in the U.S. and Europe (Ratcliffe 1988). Herman et al. (1970) estimated the peregrine population in California had declined by 95%. The California Legislature passed the California Endangered Species Act in 1970 and the Federal Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973 (Walton et al. 1988). The Peregrine Falcon was listed on both. Population declines continued into the 1970s (Kiff 1988). The cause of the decline was the pesticide DDT, an effective and affordable insecticide (Ratcliffe 1988). DDT was used extensively in the U.S. and Europe prior to the 1970s (Kiff 1988, Newton 1988). Intense scientific research discovered DDT/DDE bio-accumulated in the adipose tissue of the falcons. During the egg laying period of the breeding cycle DDT/DDE was transferred to the shell gland and resulted in eggshells much thinner than normal. The eggs generally failed due to breakage under the weight of the female or they simply dehydrated (Cade et al. 1988). In response to the dramatic decline of the peregrine in the U.S. DDT was banned in 1972. The Pacific Coast Recovery Plan (PCRP) of 1982 detailed the recovery goals for the peregrine in the western United States. California was required to have 120 pairs and a fledgling rate of 1.5 young per successful site for five years (Walton et al. 1988, USFWS 1982). The Peregrine Fund and the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group (SCPBRG) produced and released at least 6,000 peregrines nationwide during the major recovery period of 1975 to 1995 (Cade and Burnham 2003, Patte 2006). By the mid-1980s peregrines were making a strong comeback (Murphy 1990). The remarkable recovery continued and culminated in 1999 when the American Peregrine Falcon was removed from the Federal Endangered Species Act of 1973 (USFWS 1999). In California the peregrine population has also increased dramatically. By 2006 the number of known nest sites was 271, surpassing the recovery goal of 120 nest sites by 151 (SCPBRG 2006, CDFG 2007). Stewart (2007) presently reports that California has 308 known and suspected peregrine nesting sites. The fledgling rate has also exceeded the recovery goal of 1.5 young per nest, to a rate of 2.13 young per nest (SCPBRG 2006, CDFG 2007). Due to the high population numbers and increased fledgling rate, the California Department of Fish and Game has listed the Peregrine Falcon as recovered (CDFG 2007). The American Peregrine Falcon in the state of California should be removed from the CESA based on current scientific population data and evidence.

The purpose of this petition is to evaluate the current reproductive and population status of the American Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) in California. This evaluation will determine if the delisting of this falcon from the California List of Endangered Species is justified. The Peregrine Falcon in California was included as an endangered species in the CESA of 1970 (Walton et al. 1988). The Pacific States American Peregrine Falcon Recovery Team (PSAPFRT) (1973) listed the following values as primary recovery objectives for the Pacific states: 120 pairs of Peregrine Falcons for California, 30 pairs for Oregon, 30 pairs for Washington and 5 pairs for Nevada, with a yield of an average of 1.5 fledglings per year for at least five years (Walton et al. 1988). The Peregrine Falcon in the state of California has met all the recovery goals (Stewart 2007). The number of active sites has exceeded the recovery goal by more than 180 breeding pairs. Since 1992 the average fledgling rate of 2.13 young per successful pair has surpassed the recovery goal of 1.5 young per successful pair (SCPBRG 2006). The USFWS delisted the Peregrine Falcon on August 25, 1999. The overall recovery goal for the U.S. and southern Canada was 631 pairs. There were at least 1,650 peregrine breeding pairs in the U.S. and southern Canada as of 1998, surpassing the recovery goal by more than 1000 pairs (Peregrine Falcon Management Plan, PFMP, 1999). The state of Washington has already delisted the Peregrine Falcon (Hayes and Buchanan 2002). Some states, including Arizona, Utah and New Mexico, never listed the peregrine as an endangered species. Montana initiated a petition to delist the peregrine in 2005 for the following reason: “The purpose of this amendment is to remove Peregrine Falcons from the state’s endangered species list since the species has exceeded recovery goals in Montana,” reports Montana Game and Fish (2005). Subsequently, the peregrine was delisted in 2005 (Feldner pers. comm. 2006). In the spring of 2005 the Peregrine Falcon was officially removed from Vermont’s List of Threatened and Endangered Species (Vermont Institute of Natural Science, VINS 2006). The Peregrine Falcon was on Illinois' endangered species list until 2005, when it was reclassified as threatened; full delisting is anticipated as more natural sites are re-occupied (Field Museum 2005). In 1993 the peregrine was down-listed from endangered to threatened on Colorado's list of threatened and endangered species. This was followed by its removal from the list in 1998 (Colorado Department of Natural Resources, CDNR 2006). On April 13, 2007, Oregon became the most recent state to delist the peregrine (NAFA 2007). Every year additional states delist the Peregrine Falcon due to increased population numbers and recovery goals that have been met. This report on the status of the American Peregrine Falcon has been prepared to provide the California Fish and Game Commission with sufficient scientific evidence to proceed with the delisting process. The information provided herein should be more than adequate to justify the removal of the American Peregrine Falcon from the CESA. The following excerpt from the California Code of Regulations (CCR 2006) states the criteria for a valid petition: Section 2072.3: “To be accepted, a petition shall, at a minimum, include sufficient scientific information that a petitioned action may be warranted. Petitions shall include information regarding the population trend, range, distribution, abundance, and life history of a species, the factors affecting the ability of the population to survive and reproduce, the degree and immediacy of the threat, the impact of existing management efforts, suggestions for future management, and the availability and sources of information. The petition shall also include information regarding the kind of habitat necessary for species survival, a detailed distribution map, and any other factors that the petitioner deems relevant.” The petitioner has made every effort to meet the criteria established by the CCR for the delisting process. The data presented in this petition is a compilation of peregrine research by raptor biologists and others from the 1940s to 2007. Three experts in the field of raptor biology have reviewed this document and provided comments and support: Dr. Robert Mesta, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tucson, Arizona; Dr. Bruce Taubert, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix, Arizona; and Dr. Clayton White, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

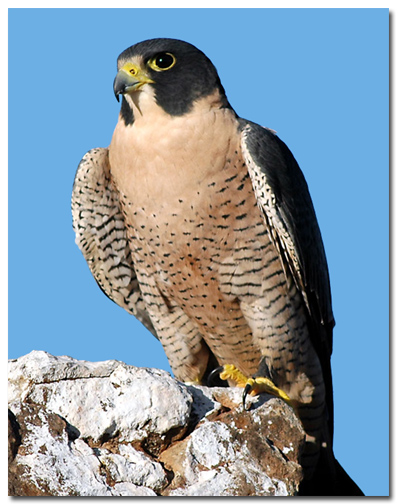

A great deal of information is currently available on the life and natural history of the Peregrine Falcon. A brief summary follows: The Peregrine Falcon is regarded as the fastest flying bird, attaining a measured diving speed of 242 mph (Franklin 1999). This species is superbly adapted for speed with its long wings, strong feathers and an aerodynamic body shape. In a dive, a peregrine can “morph” its shape by rolling its shoulders into the body, allowing for even faster speeds (Franklin 1999). Peregrines are typically sexually mature and may begin breeding at two years of age. The average life span for a peregrine is 13 years (Dewey and Potter 2002, White et al. 2002). The falcons are “reverse sexually dimorphic” in size with the females being about 1/3 larger than males (Cade 1982). The female weighs about 850 grams (30 ozs); males are approximately 570 grams (20 ozs). The female is capable of taking larger quarry and defending the nest from larger predators. A general color change occurs after the first year. This is apparently used by adult falcons to recognize other mature individuals as potential mates. Immature birds are brown; adults are a bluish black with prominent malar stripes. Some adult individuals are described as “fully capped,” meaning their head color is entirely black. In flight the peregrine exhibits a color pattern called “counter shading.” The falcon is light on the ventral surface and dark on the dorsal surface, an apparent adaptation for predator avoidance. Adults have dark yellow legs, feet, and cere. This yellow color brightens during the spring, signaling the onset of the breeding season. Peregrines use their tremendous speed to catch a variety of birds including pigeons, ducks, shorebirds, and passerines. They climb to great heights and dive at the prey, striking or grabbing with their large feet. Sometimes the hind talon, called the hallux, is used to strafe or decapitate the prey. Their large feet have long toes and sharp talons, an adaptation for catching and carrying the captured bird in the air. The bird is hauled to a plucking perch and if not dead, it is killed with a bite to the neck. Falcons have a “tomial tooth” or notch in their beak that is a unique adaptation for breaking the neck of their prey. Peregrines typically nest on high cliff ledges, digging out a “scrape” with their chest and feet. A scrape is a hollowed out area in the sand, gravel, or other loose substrate the ledge provides. Courtship begins in early spring with the male arriving at the nest site first. Most peregrines in California are year-round residents (Brown 2006) and therefore both birds are present when courtship begins. Courtship flight displays are spectacular to observe as the male repeatedly dives at his mate from great heights. Food transfers begin when the male presents the female with a variety of small birds. This encourages her to copulate and scrape in a nest site he has chosen. (Jack Stoddard pers. comm. 2000 states that the food transferring behavior was one pivotal aspect in producing captive-bred peregrines). She may accept his site or seek her own. Once a nest ledge is selected the breeding behavior continues. The falcons copulate often during the courtship period and laying of the first egg follows a few weeks later. Egg-laying generally takes seven to ten days depending on the size of the clutch. Most often three or four eggs are laid. The time between the first and second egg is about 50 hours, while the time span between the third and fourth egg could be as long as 72 hours (Burnham et al. 1978). If the first clutch fails, a second or third may be produced if the female is still in a reproductive cycle. The female generally begins incubation after the third egg is laid (Stoddard pers. comm. 2000). Both adults participate in incubation. The female incubates at night and late morning, while the male usually incubates in the early morning and early afternoon (Alten pers. observ. 2000). When the female is incubating, the male brings her food (Cade 1982). Incubation takes a total of 34 to 35 days: the eggs normally pip in 32 days and hatch 48 to 50 hours later (White et al. 2002). While the eggs are hatching the female stands over them very lightly and the male is noticeably anxious. Once the chicks hatch the female broods them while the male secures their prey. After about ten days the chicks are able to maintain their own body temperature and then she may help the male capture prey. Fledging of the young occurs as early as 35 days with males. The larger and heavier females require more time to develop and fledge around day 42 (Blood 2001, Sherrod 1983). The young falcons fly and play around the nest site for four to six weeks, learning the flying and hunting skills they will need to survive. As their education progresses, the young are taught to take injured prey from their parents. The young falcons begin to disperse as they grow more independent. They leave the nest site at 10 to 12 weeks old (White et al. 2002).

RANGE TERRITORY, AND ABUNDANCE The range of the Peregrine Falcon is cosmopolitan. The peregrine inhabits rocky coasts and interior mountain ranges in all continents except Antarctica (Ratcliffe 1993). There are 18 or 19 subspecies of peregrines around the world, depending on current taxonomy. The European population is estimated at 5,633–6,075 pairs. This represents approximately one-fifth of the world population (Hagemeijer and Blair 1997). The world population of peregrines is conservatively estimated at 30,000 pairs. The North American Peregrine Falcon (F. p. anatum) is found in 41 of the 50 U.S. states. They do not breed in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Dakota (Appendix II, North America Range Map) or West Virginia. One North American subspecies is highly migratory: the Arctic Peregrine (F. p. tundrius) travels from the Arctic to South America for winter and returns in spring. Peregrines have established nesting populations in the Arctic and as far south as Tasmania, South Africa and the Falkland Islands (Blood 2001). A “breeding/active territory” is an area that contains nesting ledges occupied by a mated pair of falcons (Postupalsky 1974). An “occupied territory” would have at least one adult present. (One source of confusion in this standard terminology is that USFWS will refer to an “occupied territory” as meaning an active pair.) The rate of territory occupancy is calculated as percentage of the total known territories where falcon behavior indicates an active site. Breeding behavior would include a copulating pair and/or the presence of eggs or young (Postupalsky 1974). A 1991 survey estimated nearly 1,600 breeding pairs in Great Britain and Ireland (Ratcliffe 1993). For American Peregrine Falcons, the known number of occupied eyries in 1997 was 301 in Alaska; 347 in Canada; 329 in Washington, Oregon, and California (USFWS 1998). The USFWS survey in 1998 found 1,650 breeding pairs in the United States and Canada, while White et al. (2002) reports over 2000 breeding pairs in the U.S., with just as many “floaters” (unpaired individuals) of various ages. Several thousand breeding pairs have been estimated in the Arctic (Blood 2001). Patte (2006) has provided the following information for the U.S. The percentage of the monitored territories occupied by a pair of peregrines varied from 78 percent to 95 percent across regions and averaged 87 percent for the nation. The percentage of occupied territories that managed to successfully raise at least one chick ranged from 64 percent to 78 percent across regions and averaged 71 percent (Patte 2006). Additional data documented that the total number of nesting pairs for peregrines in North America is estimated at 3,005 (USFWS 2003). The estimate of 3,005 pairs in North America is similar to the 2,500–3,000 pairs estimated by White et al. (2002). The North American population figures should be considered conservative estimates because not all areas were reported on (USFWS 2003). These figures include estimates of 400 pairs in Canada, 170 pairs in Mexico, approximately 1,000 pairs in Alaska, and the balance distributed among 40 of the lower 48 States (USFWS 2003). The number of young actually produced varied from 1.45 to 2.09 per successful site regionally and averaged 1.64 for the nation (USFWS 2003). Fledgling rates typical of stable or expanding populations range from 1.0 and 2.0 young per active site (White et al. 2002). Most historical (pre-1940s) and recent fledgling rate estimations fall within that range (Hickey 1942, Mesta 1999). Recovery and re-occupancy of historical sites were well underway by 1980 (Murphy 1990, White et al. 1990). During the recovery period, about 6,000 peregrines had been released throughout the country (Patte 2006). According to the USFWS, the peregrine population currently is secure; the population continues to increase as it has for the last 30 years (USFWS 2006). In the late 1990s North American breeding populations were increasing at 5–10%/yr (Enderson et al. 1995, Mesta 1999). Under favorable conditions, local density can reach 1 pair/10–20 km2 or higher, but 1 pair/100 to >1,000 km2 is more typical for North America (Ratcliff 1993). While these figures (Chart 1) do represent the national population, they are relevant in demonstrating an increasing population trend. The historical (pre-1940s) population estimate of Peregrine Falcons in North America is about 5,000 individuals (NWT Wildlife 2007, Peterson 1988). However, Kiff (1988) reports North America could have supported 7,000-10,000 peregrine nesting territories. This increasing population trend includes the current status of the American Peregrine Falcon in California that will be discussed later in the petition.

Mortality rates for first year falcons vary widely. VerSteeg (2004) reports 46% from his banding data in Colorado, while Mesta (1999) sites 62.5% for Alaska peregrines. The generally accepted percentage has been 75% mortality for the first year and 25% for subsequent years (Sherrod 1983, Steenhof 1983, Raptor Resource Project 1998). Mortality for first year falcons is generally high due to a great variety of causes. Young peregrines are vulnerable to a variety of avian and terrestrial predators. Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) and the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) are two of the main avian predators. Great Horned Owls catch the young falcons at night in roosting areas, while Golden Eagles can kill and eat them at the nest site or as they are learning to fly. Other avian predators include the Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii) and Prairie Falcon (Falco mexicanus). Terrestrial predators include the Bobcat (Lynx rufus), Mountain Lion (Felis concolor), Coyote (Canis latrans) and a variety of other mammals (Burnham 1993). Weather can be a population-limiting factor during breeding. Early storms can blow across the cliff face and sweep the young from the nest ledge (McCallum pers. observ. 1968). Unusually cold spring conditions can freeze newly laid eggs where incubation has not started. Occasionally, a nesting site is selected below ephemeral waterfalls and during springs of high precipitation the eggs or young are washed from the ledge (Mearns and Newton 1988, Fenske pers. comm., Alten pers. observ. 2002). Ratcliffe (1993) noted that adverse weather can lower the breeding success in a region. Young peregrines sometimes fatally crash as a result of novice flight skills. (Cooper 1978). Peregrines have been known to hit power lines, cars, barbed wire fences, large glass windows on buildings and just about any other standing object that might block their flight path. Most “raptor rehabilitators” are familiar with falcons that have injuries resulting from a collision. Some are released back into the wild while others are used for educational purposes. Electrical towers may cause electrocution of falcons and other raptors (Olendorff et al. 1981). About a quarter of all power outages in California are due to bird and wildlife electrocution. Recently, the power companies have taken note and have constructed towers and line placement to help reduce the possibility of raptor electrocution. Many of the outages caused by bird electrocutions involve raptors protected by state and federal laws. These outages cost nearly $3 billion a year in repairs (SCPBRG 2006). Alleviation of this problem is a savings both to the raptors and the power companies. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have recently begun to prosecute and fine companies for these avian deaths. The California Energy Commission (CEC) is taking the lead in addressing the problem in California (SCPBRG 2006). Diseases and parasites are found in all populations of peregrines (Cooper 1993). Healthy falcons are able to survive with some types of minor infestations. Other diseases are fatal, including malaria, frounce, and aspergillosis. The West Nile Virus and the Asian Bird Flu may strike down an individual falcon but do not jeopardize the population. Peregrines are solitary birds that do not live in flocks. Jay Sumner (2006) reports: “The only other disease threat to Peregrine Falcons right now is the potential for West Nile Virus (WNV), but they don't seem to be very susceptible to it, peregrines feed almost exclusively on birds. We don't have any concrete or formal testing program. We have not seen a problem with it" (Babcock 2006). A few cases suggest peregrines can be susceptible to WNV but apparently vary in their abilities to develop immunity to the disease (USFWS 2003). In September 2002, a moribund two year-old peregrine was picked up in New Jersey; it died two weeks later. Extensive tests showed definite exposure to and probable death from West Nile Virus (USFWS 2006). However, among the wild raptors in New York State found dead in 2003 not one of the 18 Peregrine Falcons tested positive for WNV (Miyoko 2003). The Asian Bird Flu (ABF) has not yet been documented in the U.S., but several sources have reported the culling of 37 falcons in Saudi Arabia. The ministry reported that the falcons, including the five positive cases, “were killed and burned” (Arab News 2006). The U.S. Customs is making every effort to prevent ABF from spreading to the U.S. Occasionally a falcon is shot by a hunter despite improved raptor education and costly fines. If either mate is killed, or dies, the remaining falcon must find a new mate. In the wild there exists a surplus of adult falcons, called floaters (Mesta 1999). Floaters fill voids in the breeding population when a mate is lost. This particular kind of impact is minimal. Rock climbing and other human activities occasionally disturb nesting peregrines (Lanier and Joseph 1989). At historical breeding sites including Morro Rock and Yosemite’s El Capitan, the cliffs are listed as “do not disturb” or simply closed. Most climbers are respectful of nesting peregrines and avoid bothering them deliberately. The following rock climbing areas in California are officially closed during the peregrine breeding season: Area 13, Clarks Canyon, Lover's Leap, Sequoia National Forest (Chimney Rock), Yosemite National Park and Pinnacles National Monument (Access Fund 2006). To minimize human activities at historical nest sites U.S. Forest Service, California Fish and Game and USFWS generally post seasonal restrictions and publish pamphlets warning hikers and climbers of local breeding areas and allow the peregrines to nest undisturbed (Access Fund 1997; Attarian and Pyke 2000). Nest abandonment due to disturbance by humans is minimal. Falconers and egg collectors have returned to the same sites year after year, and the peregrines are usually nesting somewhere on the same cliff or nest ledge (Ratcliff 1993). In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, a peregrine nest box was placed on the outside ledge of the 15th floor of the Rachel Carson State Building in 1996. Peregrines began using the nest box in 1997 and were successful in 2000. Pennsylvania’s Game Commission (PGC) Biologist, Dan Brauning, generally removes three of the four young falcons from this nest every year for banding and education. He bands one of the nestlings while he is on the ledge and leaves it there to minimize upsetting the adult peregrines (PGC 2006). The year 2003 marked the fourth consecutive year that the adult peregrines had produced four young. Every year for the past six years the nestlings have been removed from the nest, banded and replaced; the adult falcons continue to return (PGC 2006). Morro Rock has a long Peregrine Falcon history dating back to the early 1900s. The following provides additional evidence that nest abandonment caused by raptor biologists, falconers, and rock climbers has only a modest impact. Raptor biologist Brian Latta had his tenth anniversary climb of the Rock in 2000 where he bands chicks and collects data (Sullivan 2006). Scientific collection of data from this nest site has occurred for at least 16 consecutive years. The peregrines have never abandoned this site and by 2004 two pairs had established successful nesting territories. One site is located on the south side and the other on the north side of the Rock (Sullivan 2006). Lastly, the bibliography of Dr. Pagel from SCPBRG (2006) states he has entered over 160 different Peregrine Falcon nest sites during his career. He has also made almost 900 separate entries into active nest sites to collect addled eggs or fragments of eggshells, prey samples, blood samples, band nestlings, and enhance nesting substrate (SCPBRG 2006). Two significant conclusions can be inferred from active nest site disruption for data collection. Firstly, raptor biologists continue to enter active nest sites without apparent abandonment of the nesting activity/site. Secondly, the peregrine has continued to expand in range and population despite intensive regional and national scientific research. The petitioner notes too much human intrusion could certainly be detrimental to breeding success: in the 1970s when Morro Rock was one of the few known active sites in California, birders and falcon enthusiasts sometimes kept the breeding falcons off their nest for three to five hours at a time (Alten pers. observ. 1975). Secondly, while scientific data collection is deemed necessary, the prolonged duration of nest intrusion is certainly not conducive to nesting behavior and may in fact jeopardize fledgling success. The Hawaiian Crow (Corvus hawaiiensis), also called the Alala, is a case in point; the bird has been literally studied and researched to extinction in the wild. Currently, only 50 remain alive in captivity (Walters 2006). Construction of roads and rock quarries requiring blasting could indeed cause nesting peregrines to abandon their nest (USDI 1976). If the blasting were short term and the disturbance were held to a minimum, the peregrines would probably continue to breed or return the following spring (USDI 1976). Peregrines have been known to nest in active rock quarries (Pruett-Jones et al.1980). In Arizona, on Mt. Lemmon, resurfacing of the mountain road was curtailed for a period of time to allow the peregrines to breed (Alten pers. observ. 2002). The road construction crew was permitted to work only in areas deemed far enough away from known nesting sites and “no blasting area” signs were posted by nests adjacent to the road (Riordan pers. comm. 2002, Alten pers. observ. 2002). This precaution was undertaken by the Arizona Game and Fish and the U.S. Forest Service as mandated by federal law. Egg collectors in the past caused the deaths of hundreds of unborn peregrine chicks (Peterson 1988). One Boston oologist was reputed to have 180 sets of peregrine eggs, over 700 eggs from just one egg collector (Peterson 1988). Peregrine egg sets of 80 to 100 were typical of the time. The peregrine’s eggs were so valuable that one nest site was entered by 30 different egg collectors in one day (Peterson 1988). To save the eggs from oologists, falconers would sand the eggs or daub them with India ink destroying the value of the egg collection. Today the Migratory Bird Treaty Act prohibits the taking of eggs and provides serious penalties for doing so. Peregrines have adapted to biological population-limiting factors and have an incredible tolerance for human disturbance. While biological and human factors may cause minor population fluctuations, DDT has been the only significant factor that has jeopardized their existence (Cade et al. 1968, Cade et al. 1988).

From the legalized persecution of Peregrine Falcons during World War II in England, to bounties posted on peregrines and raptors in the early 1900s in the U.S., the falcon has shown remarkable reproductive resilience. It was the insidious nature of DDT that destroyed the peregrines’ ability to reproduce. DDE, a metabolite of DDT, prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation. This results in thin-shelled eggs that are susceptible to breakage during incubation (Hickey and Anderson 1969, Patte 2006, Ambrose et al. 1988). The peregrine’s population decline from DDT started as early as the late 1940s and continued into the 1970s (Kiff 1980). Initial evidence of DDT/DDE contamination for California started between 1948 and 1950, when five peregrine eggshells were collected and analyzed for the presence of DDE in their dried membranes (Peakall 1974). To determine DDE levels, ratios of DDE in the egg contents to DDE in the membranes were calculated. The following values reflect concentrations in µg/g wet weight of DDE in the egg contents calculated from those five eggshells: 7, 3, 9, 30 and 4 (USGS 2006). The DDE found in peregrine eggs at least as early as 1948 had concentrations high enough to account for eggshell thinning (USGS 2006). DDE was found to significantly affect hatchability at geometric mean concentrations greater than 3 µg/g wet weight in the egg (USGS 2006). The Ratcliffe Index is one type of standard eggshell thickness index. It is determined by the weight of the eggshell (mg) divided by the length (mm) times the breadth (mm) (Ratcliffe 1967). Eggshell data for British Peregrine Falcons from 1900 to 1945 revealed that eggshell thickness averaged 2 mg/mm. After 1945, however, there was a startling drop in the thickness to 1.5mg/mm (Ratcliffe 1967). Ratcliffe had made a significant discovery: after 1945 eggshells became thinner and more likely to break (Nelson and Morton 2006). Actual eggshell thickness for pre-1947 data in California ranged from 0.365mm to 0.369mm measured from a standard micrometer (Fyfe et al. 1988). California Peregrine Falcon eggshell data from the 1950s to the early 1980s reflected a range of 18% to 20% thinning, averaging 0.300 mm (Monk et al. 1988). This degree of eggshell thinning typically resulted in reproductive failure for peregrines (Anderson and Hickey 1972, Peakall and Kiff 1979). Peregrine populations which experienced an average of 17% eggshell thinning appeared invariably to decline (Kiff 1988). Across the U.S., one state after another began to note declines in their peregrine populations. Along the Hudson River in the 1950s all reproduction stopped (Herbert and Herbert 1969), Massachusetts had complete failure of all 14 known pairs and broken eggs were noted for the first time in 1947 (Hagar 1969). Pennsylvania noted the decline between 1947 and 1952 when the fledgling rate dropped from 1.25 young per nest to 0.3 young per nest (Rice 1969). California was not immune to the silent kill of DDT. Falconers and egg collectors noted inactive nest sites that had been consistent producers through the late 1940s and early 1950s (Kiff 1980). Even the Channel Island Peregrine Falcon became extinct by the mid-1950s (Kiff 1980). By 1965 the peregrine had been extirpated east of the Mississippi in both the U.S. and Canada (Berger et al. 1969). Fewer than five active sites in California were reported by Herman et al. (1970). The Peregrine Falcon populations continued to decrease at a disturbing rate in North America and Europe. In 1965, at the historic Madison Conference, Ben Glading and Morlan Nelson reported a well established decline of the peregrine population for the U.S. and Europe. In 1970 the California Legislature passed the Endangered Species Act, a precursor to the Federal Endangered Species Act passed in 1973. The Peregrine Falcon was listed on both. The maximum reduction in peregrine population density probably occurred from 1973–1975 (Kiff 1988). This excerpt from USFWS (1999) provides a summary of the Peregrine Falcon decline across the county starting in the 1940s: “It is estimated that prior to the 1940s, there were approximately 3,875 nesting pairs of peregrines in North America. In the Pacific States: by 1976 no American Peregrine Falcons were found at 14 historical nest sites in Washington. Oregon had also lost most of its Peregrine Falcons and only 1 or 2 pairs remained on the California coast” (USFWS 1999). In the 1970s the Peregrine Falcon was a raptor on the verge of extinction.

PRESENT PEREGRINE POPULATION TREND AND STATUS IN CALIFORNIA The USFWS (1999) report also provides this information about the current population trend in the Pacific States, including California: “Surveys conducted from 1991 to 1998 indicated a steadily increasing number of American Peregrine Falcon pairs breeding in Washington, Oregon, and Nevada. Known pairs in Washington increased from 17 to 45 and in Oregon from 23 to 51. The number of American Peregrine Falcons in California increased from an estimated low of 5 to 10 breeding pairs in the early 1970s to a minimum of 167 occupied sites in 1998. The increase in California was concurrent with the restriction of DDT and included the release of over 750 captive reared American Peregrine Falcons through 1997” (USFWS 1999). (Appendix III, California Range Map) A brief history of the peregrine’s recovery and current population trend follows: as mentioned, S. G. Herman began to study active nesting sites of peregrines for California in 1970, noting fewer than five. By 1980 there were 80 active sites (Walton et al. 1988). In 1998 there were a minimum of 167 occupied sites. Presently, SCPBRG lists 271 sites (Chart 2) in California that have supported an active breeding pair at least once since the 1970s (SCPBRG 2006). The same study documents that 30 new sites were discovered and 154 sites had confirmed active pairs. The average fledgling rate was approximately 2 young per pair at successful sites, with a minimum total of 146 young produced (SCPBRG 2006). The report also states that not all nesting territories were surveyed during the nesting season and many other young not counted fledged during 2006. Lastly, the survey was designed to record the number of pairs (over 300 known and suspected sites) and not reproductive output (SCPBRG 2006, Stewart 2007).

From 1975–1992 reporting on 1,046 pair-years, the fledgling rate was 1.10 in California (Linthicum and Walton 1992). From 1993–1997 the fledgling rate ranged from 1.4 to 1.7 young/pair (mean 1.6, n = 356 pair-yrs, Mesta 1999). California Fish and Game had contracted the SCPBRG to conduct a reproduction and population status report in 1997. At that time 190 known sites were checked and 147 sites had at least one adult present representing an occupied territory. Of those at least 111 had two courting adults representing an active territory. The fledgling rate for 81 sites averaged about 1.5 young per pair. In 1998 and 1999 about half of the 194 known territories were again monitored by SCPBRG. From 1999 to 2006 the latest population data indicates that the total numbers of peregrines in the state as well as reproductive output are continuing to increase (SCPBRG 2006). This reproductive success was facilitated by the release of 750 captive raised peregrines during the recovery period (USFWS 1999). The California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) and the SCPBRG have provided the most recent California peregrine reproduction data. A summary of the data reflects information collected from a 13 year period beginning in 1992 and ending in 2006. The population data from the years 2004 and 2005 were not available. It is reported by SCPBRG (2002) that some of the recent years’ data (2000, 2001, and 2002) may have biases that could have inflated the fledgling rates. The biases include: not knowing the true total number of nests that exist (How could we know this number?). Secondly, urban sites report more information than do rural sites (SCPBRG 2002). With the biases known and taken into consideration, the data (Table 2) are credible. The data are consistent with all other references cited and the biases are not present in the years 1992 to 1999 or from 2003 and 2006. The petitioner has no alternative but to cite these data as factual. The SCPBRG lists 14 criteria that have been established to demonstrate peregrine production during the 13 years of data collection. One of the most significant observations is the number of young produced per successful pair or fledgling rate. The recovery goal listed by the PCRP was a value of 1.5 fledglings for five years. The fledgling rate from 1992 to 2006 was never below 1.86 and the highest value was 2.72 in 2002. The average fledgling rate from 1992 to 2006 was 2.13 (1992 to 2003 equals 2.14) young per successful pair. Even if we use the criterion called “young per active site of known outcome” the fledgling rate average for the 12 year period of 1992 to 2003 was still over 1.70 young per pair. The average value of 1.70 includes 1992 and 1997 where the fledgling rate was 1.05 and 1.49 respectively (SCPBRG 2002). The data presented in Table 2 provides strong documentation and demonstrates clearly that the Peregrine Falcon population is stable and increasing in California.

The reported USFWS (1999) data in Table 1 are also substantial evidence for delisting: the Pacific Coast Recovery Plan (PCRP) recovery goal for the Pacific Coast was 185 active pairs (Table 1) (USFWS 1982) and in 1999 there were 270 active pairs. The recovery goal had been exceeded by 85 active pairs. The fledgling rate of 1.5 young/pair was also met (USFWS 1999). Table 1 also provides current active site totals for the years ranging from 2003 to 2006 (USFWS 2003, 2006). The recovery goals have presently been exceeded by 301 active sites. Additionally, Kauffman et al., (2003) used a newly developed population estimation model, the “Barker Model” to analyze the peregrine population along the mid and south Coast Ranges. They separated the population on spatial and temporal criteria. The results indicate that first-year falcons fledged in urban areas had a survival rate of 65%; however, rural first-year survival was only 28%. Two important facts stand out in the conclusion of their study: First, the urban peregrine population showed an estimated growth of 29% per year, an extremely high rate of growth for any raptor species. Secondly, their data revealed an increasing population in the rural areas. This increase was not as significant as in urban areas, but more than adequate to maintain a self-sustaining population. According to Kauffman et al., (2003) based on annual population censuses, the south-coast peregrine population appears to have recovered. Lastly, in 2004 the California Department of Fish and Game in the Habitat Conservation Planning Branch under Threatened and Endangered Birds, list the American Peregrine Falcon (F. p. anatum) as recovered. This is crucial evidence (Appendix I) that can only support delisting. |

||||||||||||||||||||